People attending Sunday’s presentation on the history of wildland fire in Florida walked away with a simple message: Fire is not the enemy.

“Of the 42 community types in Florida, 16 are considered fire-dependent,” said Raelene Crandall, a fire ecologist and associate professor at the University of Florida, who led the talk, “Keep on Burnin’: The History of Wildland Fire in Florida,” at the Hogtown Creek Headwaters Nature Center. “If we don’t burn it, we lose it.”

The talk, part of Gainesville’s Perspectives in the Park series, delved into the often misunderstood role of fire in Florida’s natural landscapes, blending Indigenous knowledge with modern science to reframe how the public views wildfire and prescribed burns.

Prescribed fire is intentional, written and managed

One of the biggest messages that Crandall reiterated throughout the talk was that prescribed fire is not the same as wildfire.

“We use the word ‘prescribed’ on purpose because that implies that we’re actually writing down what we’re going to do and planning it out,” said Crandall.

In contrast to the unpredictable destruction of wildfires, prescribed fires are carefully planned and low in intensity, often designed to mimic the natural fire cycles ecosystems evolved with.

Crandall explained that intentionally set fires help maintain forest health by reducing excess fuel and supporting species that are fire adaptive.

“Prescribed fires in our region are generally pretty low in intensity,” Crandall said. “They’re meant to support the ecosystem, not destroy it.”

Smoke is inconvenient but necessary

A few attendees expressed concern about smoke and its impact on public health and the environment. Crandall acknowledged these worries but stressed that, when it comes to intentional burns, smoke is a major component thought about during the planning process. It’s not just a byproduct, but instead it’s predicted, tracked and managed.

“We have smoke management programs that we actually use in our data, and it tells us where the smoke is going to go,” said Crandall. “And we want to make sure that we're burning on a date where the winds are moving the smoke okay from fire sensitive areas.”

One of the attendees, Cindy White, said that she had no idea there was so much foresight around smoke. She said she feels safer knowing prescribed burns aren’t just set on the fly and forgotten.

Wildlife actually benefits from fire

The Southeast is a fire adapted region. Frequent fire isn’t just tolerated here, it’s ecologically essential and many plants and animals thrive because of it.

“Some species have traits that make them very compatible with fire,” explained Crandall. “A good example is the longleaf pine. It has this grass stage where the needles are protecting its bud so that when we burn it doesn’t harm the actual bud, just the needles around it.”

Kathy DeBoer, a frequent attendees of the center’s talks, said she wasn’t surprised by the role fire plays in the ecosystem. But what intrigued her was how much can come from the aftermath of a burn.

“I knew a little bit about them [prescribed burns], but I always had some worries about the animals and plants. Now I realize how much better off they are with it,” said White.

Fire has always been part of Florida’s landscape

Humans have used fire on this land for thousands of years, and people have been in Florida for at least 14,500 years, according to Crandall.

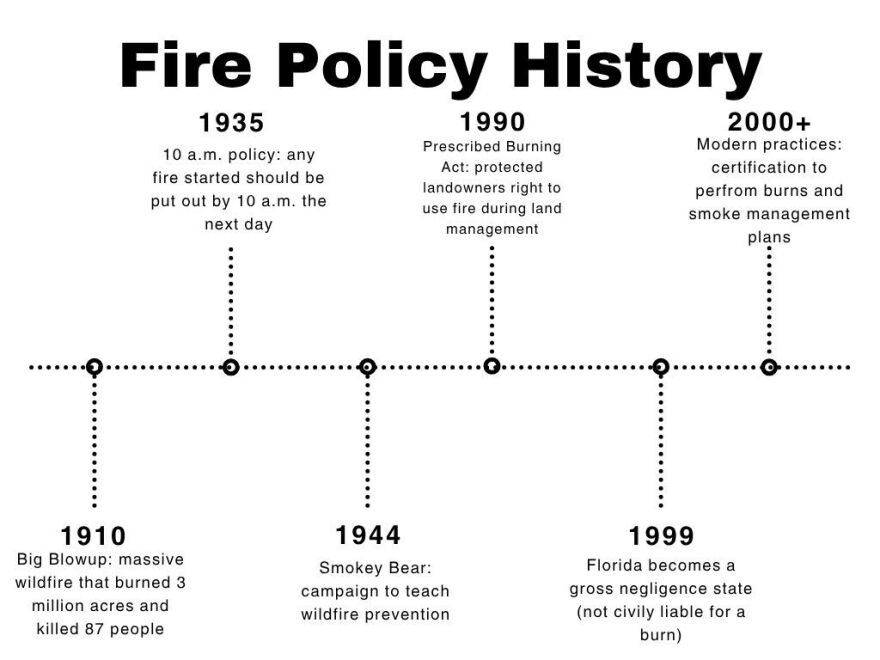

But in the 20th century, the practice of suppressing fires became dominant after hurricane winds fanned hundreds of small wildfires into a fierce inferno in the Northern Rockies of Idaho and Montana that destroyed 3 million acres, flattening entire communities and killing 85 people. The two-day firestorm became known as the 1910 Big Blowup.

“In 1935, the U.S. Forest Service instituted the 10 a.m. law which said that any fire started should be put out by 10 a.m. the next day. Then, of course, Smokey Bear was started in 1944,” Crandall said.

All of this messaging was telling the public that fire was something that should be feared and avoided. Now, the Southeast is leading the way in reclaiming beneficial fire practices.

“We burn 6 million acres collectively in the southeast U.S. every single year,” said Crandall. “Almost 2 million just in Florida.”

Still, it’s not a one-and-done solution. Prescribed fires only reduce the probability of wildfires for about two or three years, so consistency is key.

A collaborative fire future is necessary

Perhaps the most inspiring part of the talk was the spirit of collaboration among agencies, landowners and communities.

“Fire now is such a collaborative effort,” said Crandall. “Cities, state, federal organizations and even private landowners work together under shared agreements.”

What was once a fragmented response system has become a model for coordinated action. This unified approach allows the prescribed burns to help the growth of an ecosystem as well as ensure the burns are as safe as possible.

“It was interesting to hear how many different factors are brought together to make these burns possible and safe,” said DeBoer.

Fire isn’t just a threat, it’s a vital tool for protecting Florida’s ecosystems. With knowledge, planning and collaboration, prescribed burns are helping nature thrive, one careful spark at a time.