CEDAR KEY, Fla. — Capt. Chad Osteen has been fishing since he could walk. His father was a fisherman, as was his father before him.

But while the trade is in his blood, the 54-year-old charter guide still couldn’t sense what was coming.

A prized gamefish was creeping into the picture — but to Osteen, it wasn’t welcome in Cedar Key. It took over waters that were once familiar, almost upending his business with it.

They dart through the shallows, blurs of silver that give many anglers a thrill. The largest can stretch over 3 feet long and weigh more than 35 pounds. Some call them “linesiders” for the striking black streak that runs from gills to tail.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission described snook fishing as “always challenging and many times frustrating,” making a catch all the more rewarding. Popular with sport fishers, it’s heavily protected by law following past frenzies of overfishing. During the spring and fall open seasons, Florida anglers are allowed to keep one a day.

The tropical gamefish mosey in schools along the coasts of North and South America from Florida to Brazil, never venturing far from the estuaries where they grow up. During winter, they head back into inland estuaries and rivers, which offer them a refuge from frigid temperatures they can’t survive.

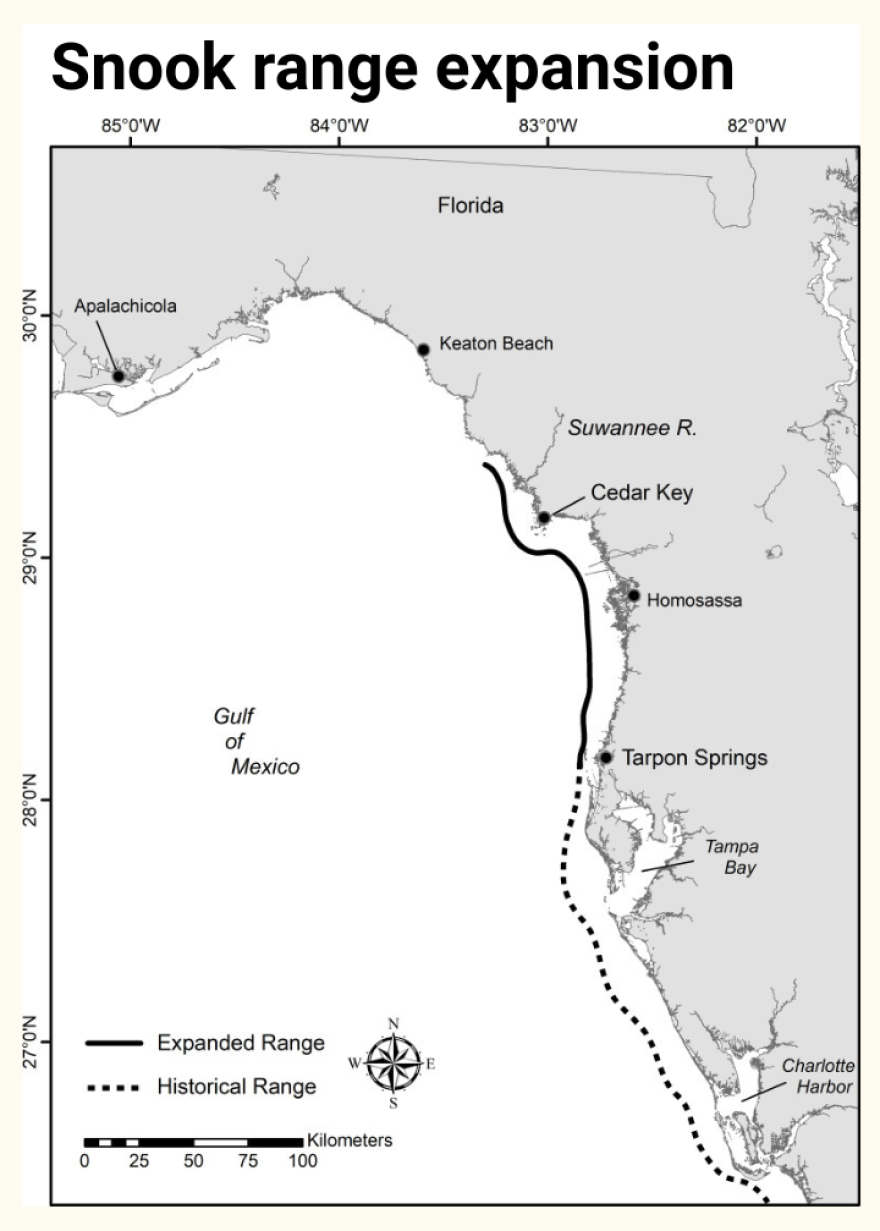

Until recently, only isolated Atlantic and Gulf groups of common snook patrolled both coasts of Florida, rarely interacting. On the Gulf side, the species rarely showed up north of Tampa Bay.

But over the past two decades, snook began to appear off Cedar Key, more than 100 miles farther. In the early years, Osteen and other local fishermen thought it was an oddity — and it was. But the snook kept coming. They followed one another up the coast little by little, slowly forming a stronghold off Florida’s Nature Coast, where they once couldn’t have hoped to survive the cold.

“And then it seems like we started catching more, and more, and more,” Osteen said.

Scientists link warmer winters brought on by climate change with the gradual snook invasion. Whether that’s good or bad for Cedar Key depends on who you ask.

The climb

While most kids went to summer camp, Osteen was always on a boat. He got his very own at 11 years old. It was 16 feet long with no name.

He helped his father with “whatever was making the most money at the time,” he said, but he didn’t look back on crabbing fondly. Crab season was a combination of sweltering summer temperatures, “nasty” decks and the smell of his father’s cigarettes. He much preferred their time fishing.

Off Cedar Key — where Osteen has spent most of his life — he made it his livelihood. He started going by “Chum,” a nickname his friends gave him for doing "stupid stuff.”

He used to be able to follow inshore marshes and oyster bars to a wealth of redfish, his most reliable catch.

“Back then, we caught redfish year-round,” he said. “It was nothing to go catch 15, 20 a day.”

But once snook moved in, everything changed. The fish he knew all but disappeared, he said, especially once he saw snook pop up around islands and sand bars. As they swarmed in, Osteen’s childhood fishing grounds seemed off kilter.

Of course, redfish faced challenges before snook arrived. By the late-1980s, the species was so overfished that FWC implemented “emergency closures” and strict bag limits, which allowed their populations to recover. However, poor water quality and habitat loss have instigated another drastic redfish decline.

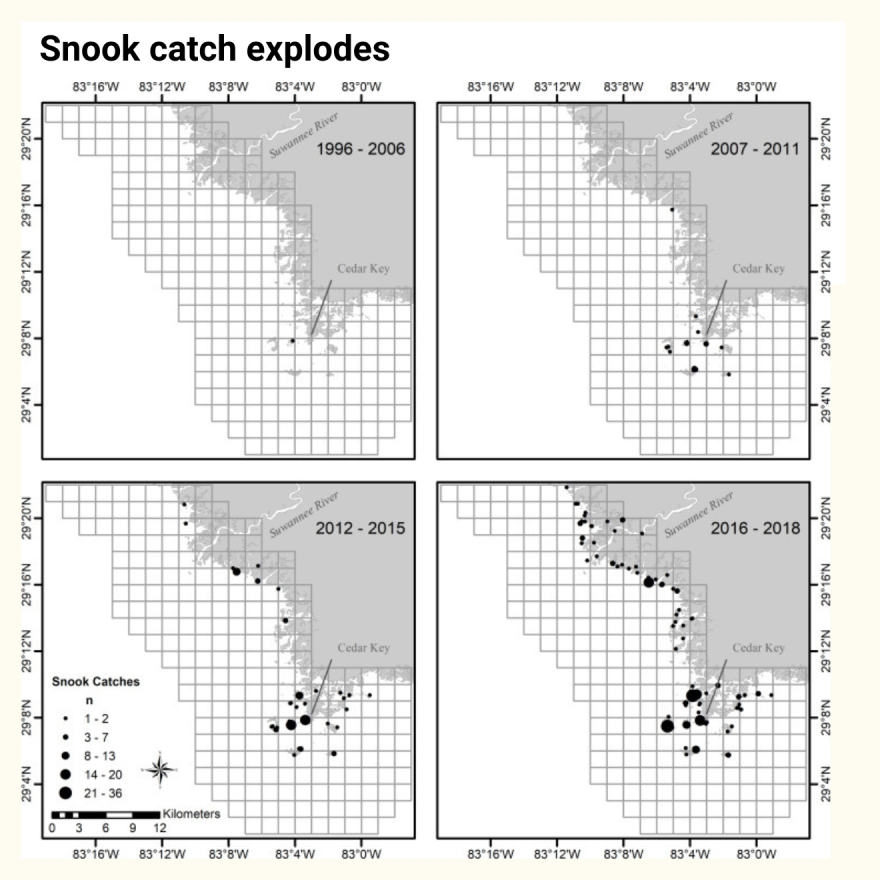

Hungry snook could still put pressure on local species looking for food, said University of Florida fisheries professor Mike Allen, who directs UF’s Nature Coast Biological Station overlooking the Gulf at Cedar Key. There was an exponential increase in catches between 2012 and 2018.

The area’s multigenerational fishermen have deep historic knowledge of the coast, he said, and they’ve never encountered the numbers of snook now seen. The Native American shell mounds that rise in the area hold no snook secrets either.

“I don’t believe the snook have ever been here like this,” Allen said. “They’ve never done this in the past.”

The same pattern is playing out across the Gulf as they swim up the coast of Texas, too.

But the silvery newcomers still have a challenge: the cold. The tropical gamefish will die if the water drops below about 50 degrees, Allen said, which happens in Cedar Key “just about every winter.”

To survive, they seek refuge in the Suwannee River and nearby springs. Both tend to be warmer than the coastal environment in winter. Groundwater burbles up from the aquifer at a near-constant 72 degrees, he said, protecting the tropical species during fall and winter.

Adult snook can tolerate the freshwater. Beyond their annual thermal refuge, Allen said some will stay in it for years. Down south, he’s even seen snook journey across the state from coast to coast through Lake Okeechobee.

They can’t reproduce in it, though. Their eggs need the salt-fresh mix of estuaries to survive. So when warm Florida weather returns, Allen said, snook make their way back out into the ocean to reproduce.

Even though occasional freezes still settle in, winters across the globe have been warmer on average. The 10 hottest years on record since 1850 have all fallen during the past decade, with 2024 striking a new record, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data. Snook moving into Cedar Key as temperatures spike is no coincidence, Allen said.

“This is a range shift due to climate change,” he said. “I don’t think there’s any doubt about that.”

Osteen wasn’t so sure. In his mind, it’s more likely that “things just have a cycle.”

Still, the multigeneration fisherman noticed it’s stayed warmer in the fall and colder into spring than what he would consider normal. That made him wonder if something is “out of whack.”

Cold snaps may become less frequent but much more intense as a symptom of climate change, according to SciLine, a nonpartisan scientific society.

Three years ago, Osteen said a freeze may have killed over half of the new snook population. He saw up to 200 lifelessly floating. It killed the mangroves and spotted seatrout, too.

“There was just dead stuff everywhere…” he said, trailing off. Still, since he predicts he’ll see another in the years to come, it’s difficult for him to attribute the occasional extreme to climate change, including the snook migration.

He’s more worried about his charter business.

Long term, he said targeting the season-limited gamefish is much less dependable than sticking to redfish or spotted seatrout that can be caught and kept year-round in the Big Bend. The new resident species comes with a narrower per-person limit and a 5-month open season.

“If it was left up to me, I’d rather just have the redfish,” Osteen sighed.

‘Hand-to-hand combat’

Allen unmoored his personal boat, on the hunt for snook. His crew consisted of another researcher, a “local guy” volunteer and a UF sophomore who’s kept a list of every single fish species he’s ever caught — 156 as of June.

The Triple A, an abbreviation coined from the name of his family’s Texas cabin, the “Allen Attitude Adjuster,” sped away from Cedar Key.

The UF researchers work in tandem with FWC. The first step of their multipart project was to document where the new snook spawn. The teams ventured to offshore channels and wrecks, aiming to capture and catalog as many of the fish as possible.

Allen and FWC’s long-term goal: Pinpoint the parents and spawning sites of baby snook growing up in coastal estuaries. Eventually, that data could help them estimate the success of the nurseries and total population size.

The scientists can collect genetics from any snook, but it’s the females they really want. It means the possibility of an egg sample, too.

Snook are batch spawners. That means they gather in deep water to release more than a million eggs at a time — as often as every two days — all in hopes a few will end up fertilized and jetted into the estuaries that serve as nurseries.

Timing their trips to the full moon is key, Allen said. When the full moon rises, tides and currents are strongest. Snook want their eggs to reach the coast, so it’s the perfect time to spawn.

About 11 miles offshore, Allen steered the Triple A toward a “wonderland of fish,” a jumble of jagged metal barely visible during high tide. It used to be a lighted marker tower for Seahorse Reef before Hurricane Helene tore through and ripped the top clean off.

The boat lurched over choppy waves, sending its passengers grappling for purchase as they cast.

Greg Lang’s line screeched. Something had taken the bait — and it was strong. The then 63-year-old volunteer leaned back, fighting to keep the fish from getting tangled in the tower.

“This is hand-to-hand combat,” Allen said, craning his neck.

Lang followed the fish up to the bow, trying to predict its rapid changes of course. Several minutes of struggle passed before his pole relaxed. A snook pressed close to the side of the boat, its stripe stark against the blue beneath.

They netted the fish and lifted it into the boat. It went from still to flailing in an instant, and the crew scrambled into position. Allen dropped down to wrangle the fish while the volunteers grabbed clipboards and equipment cases.

“See those scissors? Take a little fingernail size cut off of here,” Allen said, pointing to one of the fins on the snook’s belly. “This is for genetics.”

They snipped and scribbled.

“It looks like it’s a candidate to be a female,” he said. “The proof is when we get eggs.”

The fish thrashed on the deck. Allen and the crew gingerly held it down as they inserted a thin, clear tube into its abdomen. They lightly suctioned and leaned forward with interest, hoping.

A moment passed. Then, pale yellow eggs rushed into the tube.

“That’s a winner!” Allen shouted.

The crew beamed. On some trips, he’s seen more than five males without stumbling across one female, he said. They got lucky, and all before dusk.

Now they sped up their steps. There was no time for excitement: They only had a few moments before the snook needed to be released.

Allen stretched the female flat, squeezing her tail as they capped both samples and jotted down her length. Measuring 36 inches long, she surpassed the 28- to 33-inch range that can be legally caught and kept during the fishing season.

But that day, the researchers planned to return every snook regardless. They lowered her into the waves, and she dashed off.

The egg sample would soon be analyzed by Alexis Trotter, an FWC assistant research scientist specializing in snook biology. Her crew was on another boat, visible just beyond the tower marker.

Trotter dropped her pole and sat cross-legged, perched on the edge of the FWC research vessel.

Cedar Key snook grow bigger and faster than Florida’s two separate Gulf and Atlantic groups, Trotter said. And even though winters have been progressively warmer, researchers found that this northern group seems more tolerant of chilly water, equipping them to survive the occasional North Florida freeze.

Most importantly, she said, Cedar Key snook are genetically distinct. They’ve formed their own, self-sustaining population.

“[They] were as distinct from the rest of the west coast as the west coast is from the east coast,” said Trotter, who is based in FWC’s St. Petersburg research complex. “It’s kind of a mind-blowing result.”

The summer trip was a sampling operation, but her work can also involve tagging. Researchers implant a device about the size of an AA battery into the snook’s abdomen. Since 2016, FWC has kept an eye on 226 snook swarming the area. About 132 are still trackable.

Acoustic receivers line Cedar Key and the Suwannee River, detecting when snook swim by. The tags ping within a few hundred feet, and all those locations and pings help the researchers track the fish for about six or more years, Allen said.

The FWC crew hooked something, and it swerved straight into the tower.

“Don’t let him over there,” Allen muttered. “Put the hammer down on him.”

The line snapped, and they all sighed.

Both boats switched their engines on, zipping toward a sunken dry dock about 16 miles offshore. It was 7 p.m., the “witching hour” for snook, Allen said, but there were no more bites that evening.

Trotter radioed in with a string of light-hearted profanities, and both crews turned back to shore, pelted with saltwater and distant thunder.

Adapt to survive

Osteen lumbered across the Cedar Key City Marina with a slight limp in July. Injured on the job a few weeks earlier, he was already eager to get back out on the water.

“I mean it is nice to catch snook because people go crazy when they catch them,” he said. “When we catch one, it’s a bonus.”

But that’s all he reckoned it needed to be: a bonus.

Osteen’s clients would rather find more keepers, he said. His charters will hit the snook bag limit — one per person — too quickly, and that’s only if the trip falls during the legal fishing periods.

For more than five months out of the year, snook have to be released. So, it’s possible his clients may leave with nothing during the offseason, especially if they can’t hook redfish.

People never historically flocked to Cedar Key hoping for snook like they do redfish, he said. And biologists once warned him snook could run the reliable hordes of those redfish out of their normal haunts, too.

“I think it has hurt us,” Osteen said, shaking his head. “It has hurt our businesses.”

Kyle Williams, a UF fisheries and aquatic sciences graduate student, hopes he can soon know for sure. His research asks whether snook and redfish are competing. So far, they appear to have different enough hunting styles not to be – at least not over food.

While redfish have jaws built to dig for crustaceans and small fish, Williams said snook have upturned jaws designed for sucking up prey.

Osteen still worried that snook had something to do with it, but he also mentioned other reasons redfish may have gone, too. The 1980s blackened redfish trend took a huge toll on the species, which can no longer be commercially caught in Florida. The oysters bars they use as feeding grounds are also disappearing, Osteen said. About 85% of Gulf oysters are gone. Scientists link their disappearance with overharvest; disasters like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill; and sediment washed in by storms, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Yet, while snook have left Osteen with lingering suspicions, others see them as a blessing.

Osteen paused, waving over a friend who was tugging his boat in. Capt. Matt Cowart wiped his hands and plopped down on the picnic bench.

Since he discovered a new gamefish in the area — which Osteen showed him — the then 40-year-old fishing guide changed everything. To figure out their patterns, he started looking in places he’d never usually pay attention to. His realization: Snook are everywhere.

“They’re on the shoreline, they’re in the creeks, they’re on the islands,” he said. “They’ve just seemed to kind of be taking over Cedar Key.”

He ventured farther offshore to “out of the box,” deep channels, switching his charter model to focus on the species. There are probably 10 different schools of hundreds that spend time off Cedar Key in the summer, Cowart said, and now he knows how to fish them.

For an angler like Osteen fond of keepers, snook are not ideal. But Cowart opts for catch and release. Most he hooks are too big to keep anyway, he said.

Now, sport fishing clients who would travel to South Florida for a chance to find snook can just stop in Cedar Key, instead.

“And they’re not catching the quality of fish that we catch,” Cowart said.

“No, they don’t come close,” Osteen added.

Plus, the new northern snook are even bigger, Cowart said, just as Trotter and the FWC had found. His clients travel to Cedar Key from all over Florida and the U.S. to see them.

As the species finds itself adapting to change, so will career anglers.

The captains left their table and meandered down the marina.

“I’m getting too old for this shit,” Osteen joked.

Cowart laughed, “Don’t tell me that. If you’re too old to fish, what the hell is next?”

UF journalism senior and FCI Student Climate Fellow Rylan DiGiacomo-Rapp reported this series with support from the Florida Climate Institute.