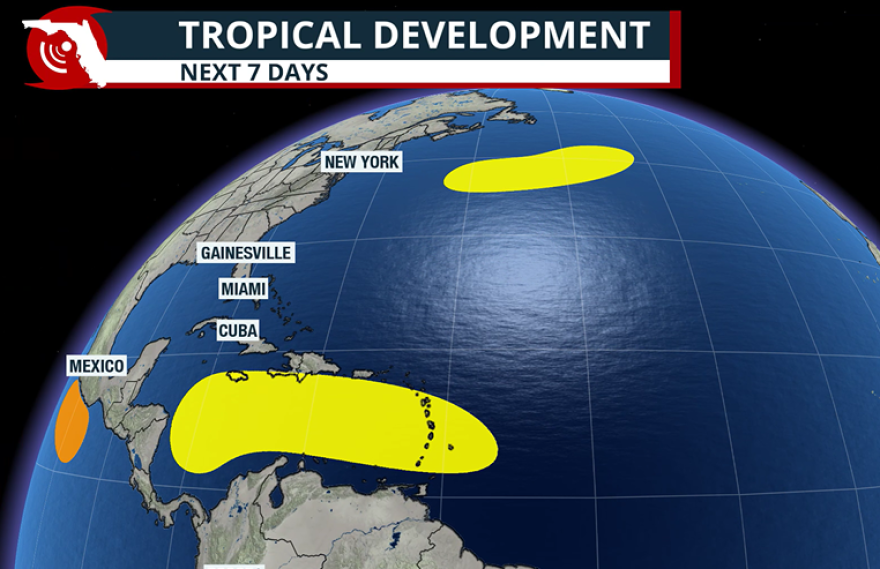

Even though the calendar says it is mid-October, the National Hurricane Center is monitoring two separate disturbances across the Atlantic basin, including a feature that will enter the Caribbean Sea next week.

Of the two disturbances, forecasters are closely watching the feature in the central Atlantic due to its longer-term potential.

The tropical wave is located east of the Windward Islands and is moving westward at a pace of 15 to 20 mph.

By next week, development chances are expected to rise, and the basin could see its next named storm - Melissa - develop south of Puerto Rico.

The Caribbean Sea is often a late-season hotspot for development, as water temperatures are sufficiently warm to support a tropical cyclone and there are periods of favorable upper-level winds.

Major computer forecast models, such as the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) and the Global Forecast System (GFS), show the disturbance developing into a potent hurricane while in the Caribbean, but the timeline for development is vastly different.

The GFS is more gung-ho and develops a center of circulation by next Thursday, while the ECMWF is a bit slower in its solution and doesn’t form a cyclone until around Saturday, Oct. 25.

When and where a cyclone forms would have significant implications for the countries located in the Caribbean, as well as whether any of its moisture reaches the Lower 48.

Due to the various scenarios at play, it is difficult to look beyond the week-plus timeframe, as the positioning of ridges of high pressure and cold fronts will be critical in determining the future movement of the potential tropical cyclone.

At the very least, rainfall across the Caribbean is expected to increase late in the weekend and next week as the tropical disturbance slows its forward motion and ponders its next move.

Second area of development in the northern Atlantic

A large storm system several hundred miles south of Nova Scotia, Canada, has a brief window for tropical development over the next week as it ventures over the Gulf Stream to the northeast of Bermuda.

Water temperatures are in the range of 70 °F to 75 °F, which could be just warm enough for the system to develop subtropical or tropical characteristics.

The NHC has kept the odds rather low for development - less than 30% over the next week.

Even if the disturbance does not develop into a tropical entity, the large storm system will continue to traverse the northern Atlantic and pose a significant threat to marine interests as it moves generally toward Europe.

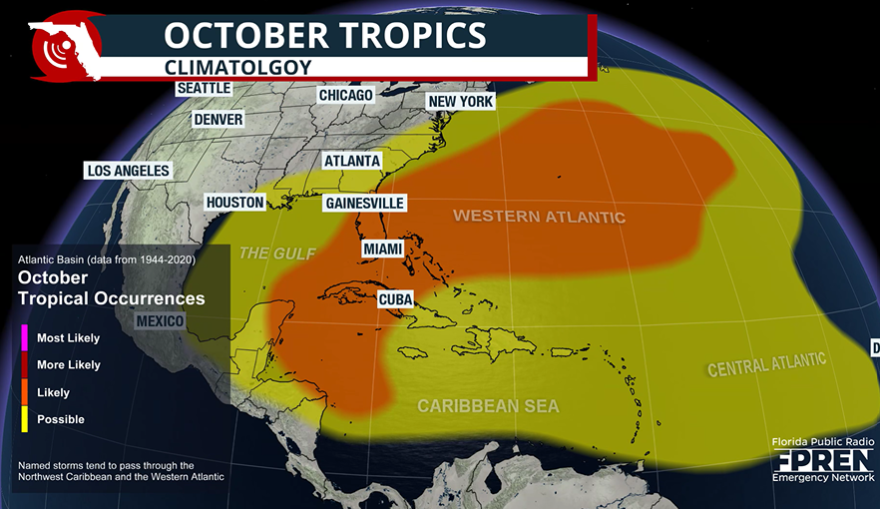

What a typical October looks like in the tropics

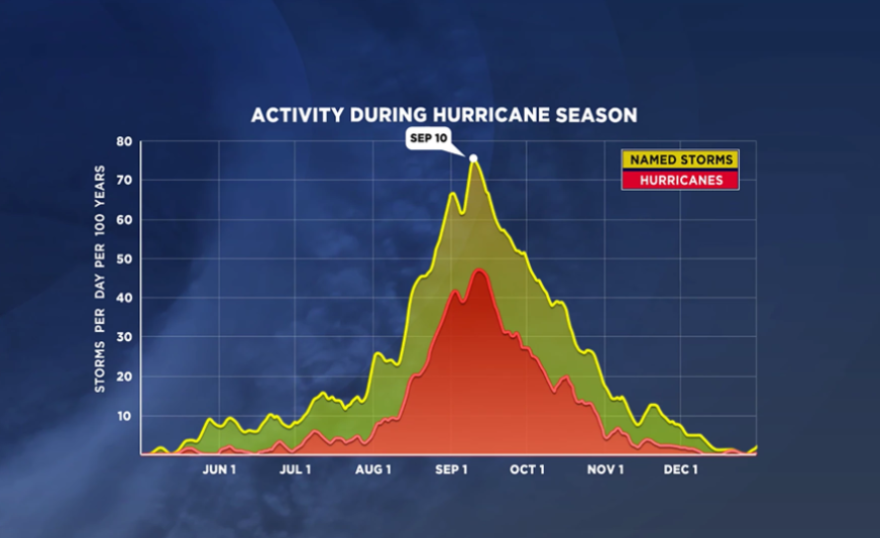

October is typically the third-busiest month for tropical activity across the Atlantic Basin, averaging about three named storms, one of which usually becomes a hurricane.

Because of the synoptic patterns that dominate the Northern Hemisphere this time of year, systems that form in the eastern Atlantic rarely make it across the basin. Instead, forecasters focus on development areas in the Caribbean, Gulf and southwestern Atlantic, which could have more significant consequences for landmasses.

When tropical cyclones form in those regions, Florida is most at risk for a direct landfall due to prevailing steering currents.

Systems that avoid being swept away by the jet stream often drift westward into Central America, where mountainous terrain and vulnerable infrastructure can magnify their impacts.

One of the most devastating late-season examples occurred in 1998, when Hurricane Mitch formed over the Caribbean in late October.

Mitch lingered for days, unleashing torrential rain and catastrophic flooding across Honduras, Nicaragua and neighboring nations. The disaster is estimated to have killed roughly 12,000 people, making it the second-deadliest hurricane in Atlantic history.

The Atlantic hurricane season runs through Nov. 30 and, so far, has produced 12 named storms, four hurricanes and three major hurricanes.