The key to a healthy, happy city is a healthy forest. At least that’s what researcher Michael Andreu believes. But now he wants your opinion.

He and his team are in the process of creating a sustainable urban development plan for the city of Gainesville. Recently, the team launched the “Your Urban Forest” online survey. It’s the second step of their project they’ve nicknamed “What do you want?” in which they try to learn if and how citizens value the city’s greenery.

According to his research, cities that maintain lively forests and a lush forest canopy make the area more livable for people and help businesses thrive. Also, a dense canopy brings several health benefits. More trees keep the city cooler, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and maintain a healthy ecosystem for wildlife.

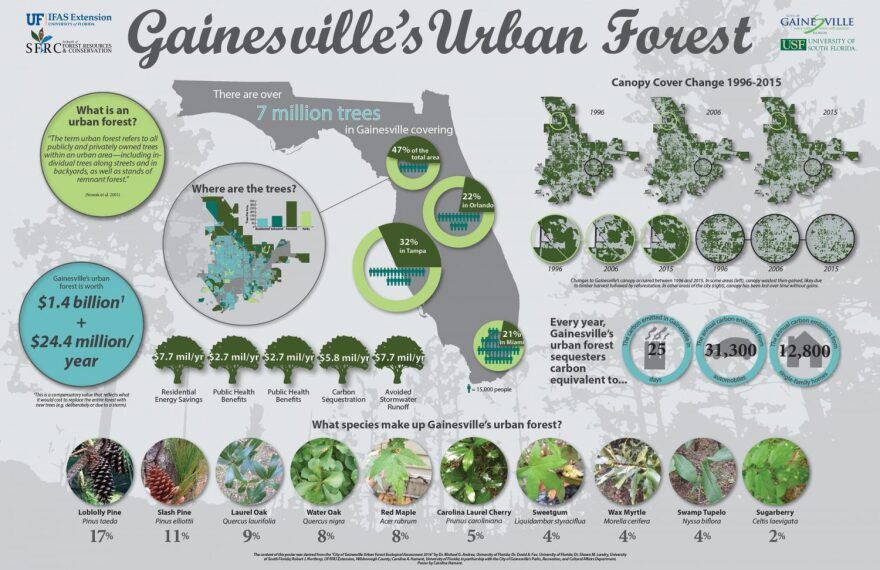

The UF professor of forest resources and conservation conducted a study that showed Gainesville has lost 11 percent of its canopy from 1996 to 2016. In a tree-loving city like Gainesville, this loss is huge to Andreu.

The study of Gainesville’s decreasing canopy was the first step in a three-step, multi-year project, Andreu said. Before he could begin anything else, he had to address what canopy the city had.

Some data, like pollution or noise emissions, can be measured in numbers and studies, Andreu said. However, other issues of interest, like people’s happiness, don’t have numerical data attached to them. The survey aims to help the team and the city quantify this otherwise uncountable data.

The survey includes questions like "How important is the urban forest to the City of Gainesville?" with sliding scale answers from "very important" to "not very important." Many questions involve ranking individuals' personal opinions on how to ensure a healthy urban forest. Rounding out the survey are personal questions about gender, jobs and income. In total, the survey is 20 questions and can be taken here.

Robert Northrop, the survey project manager, wrote and created the new social survey hoping it will provide a framework for how the city moves forward. Having citizens respond to the survey is a critical step because the people of Gainesville will determine what needs to be done, he said.

Since its launch a few weeks ago, the team has gotten about 600 responses. Although the city told Northrop and Andreu that they have enough responses to create statistically viable data, they want more. Their new goal is to have more than 1,000 responses.

The team will not look at any responses until April 8th, but even after that date, Andreu plans to keep the survey open until he believes he has heard from people beyond those who would normally respond. The team is trying to avoid any generalization in its data collection.

Carter Belvin is a Gainesville citizen who just wants his voice heard.

Belvin works at an environmental engineering firm, so not a day goes by where he doesn’t think about Gainesville’s canopy. In both his work and personal life, he values green spaces around the city and wants them to be considered as the city moves forward in developing and planning.

This survey, he said, ensures that his voice is heard. Having citizens become part of the process, Belvin said, encourages them to appreciate the success of an environmental initiative and support similar endeavors in the future.

Andreu and Northrop want to hear from more voices like Belvin’s. Although he might have a milder response in comparison to others, Northrop said, the team needs to hear opinions all along the spectrum. Andreu said the team wants to hear from every segment of Gainesville, which includes every neighborhood and hearing from all genders, socio-economic backgrounds and ethnicities.

“We really want to be inclusive as possible,” Andreu said. “The more inclusive (the survey is), the more powerful it is.”

As a citizen himself, Andreu said, he’s proud that his city values the environment, and he believes every citizen of Gainesville should be proud of their city, too. It’s easy to acknowledge that there is a problem, Andreu said, but the commitment the city and its people are making to be proactive is admirable.

“This is all about (the citizens),” Northrop said. “Everything (we are doing) is for them.”

Once they believe they have heard from everyone who wants to express an opinion, they will pass their finds to a newly created technical advisory board. This panel will establish a vision for the city’s urban forest and set goals for future sustainable development in Gainesville.

In Andreu's opinion, the project will never be officially "completed." This is just the start of a very long back-and-forth conversation between the city and its citizens.