On Both Sides Of The Dam

ON BOTH SIDES OF THE DAM

The Ocklawaha River was dammed in 1968. The flooded reservoir drowned over 7,500 acres of floodplain forest and 20 freshwater springs. Over 50 years later, people continue to fight for and against the existence of the dam.

Video and Photos by Gaby Eseverri Story by Stephanie Cornwell

March 2, 2020

[Updated April 15 at 11:20 a.m.]

ON THE OCKLAWAHA RIVER -- Marjorie Harris Carr’s coffin was lowered into the ground with a bumper sticker reading “Free the Ocklawaha” in 1997. Last year, her granddaughter Jennifer Carr held a sign with the same words as Gov. Ron DeSantis spoke at the University of Florida about the state’s pressing environmental issues. Carr hopes the fight to restore the Ocklawaha River will not drag on another generation.

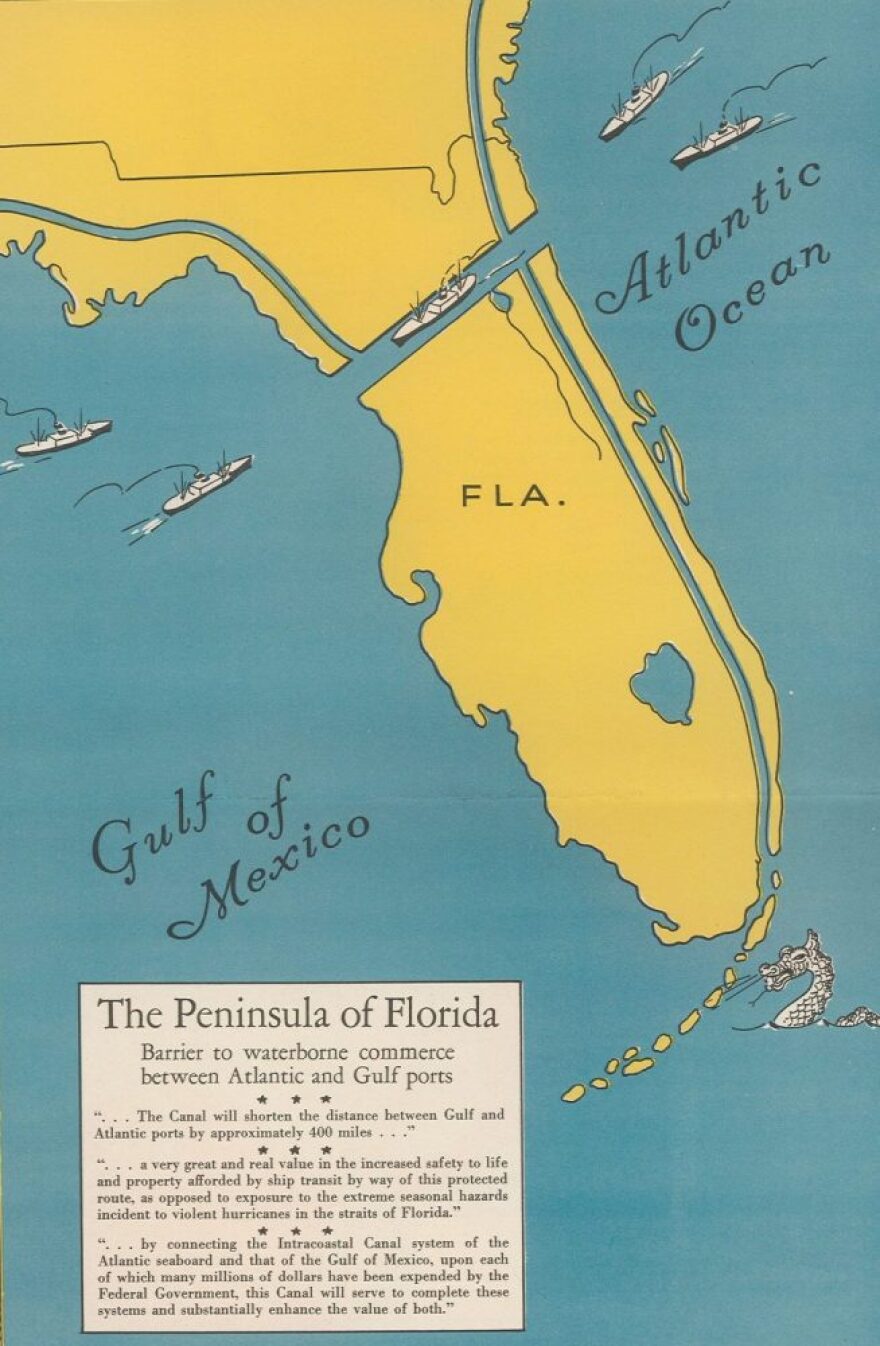

The Cross Florida Barge Canal was a dream that never happened, a navigable waterway to connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. The economic growth from a cross-peninsular canal promised something crucial to many Floridians —jobs. The Army Corp of Engineers started construction on the canal twice, once in the 1930s and again in the 1960s, and boosters believed the project would lead to growth and prosperity.

But construction of the canal came at a cost to the environment: The Rodman-Kirkpatrick dam was built on the Ocklawaha River, creating a 9,000-acre reservoir that caused destructive flooding to the surrounding forests,according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

State and federal powers met their match in Marjorie Harris Carr and the group she founded, Florida Defenders of the Environment (FDE). In 1971, President Nixon halted construction of the canal, “to prevent potentially serious environmental damage,” read thefront-page story in the New York Times that January.

But the dam was left behind, along with its flood-pool that drowned much of the surrounding vegetation and 20 freshwater springs that once bubbled up in the forest. The water rose about eight to nine feet above its natural level, rotting the trees at their knees as the roots fought to breathe.

The Ocklawaha is now ninth on America's Most Endangered Rivers of 2020 -- a list put out yearly by the conservation organization American Rivers.

Many people wonder why the dam remained once construction on the canal stopped.

“It’s been 48 dam years. Let’s not make it 50,” wrote Jennifer Carr inher 2019 opinion piece on the “unfinished business in the Ocklawaha River.”

Every battle has two sides, and it’s not always black and white.

Many environmentalists want to take the dam down and let the Ocklawaha flow freely. They want to give native fish populations and the forest a chance to grow back.

But members of Save Rodman Reservoir, a nonprofit dedicated to keeping the dam in place, don’t want to see the collapse of Florida’s natural habitat either. They say draining the reservoir would displace many species that call it home, along with the people who recreate there.

And many Putnam County locals don’t know life without the reservoir and the fishing it provides. Rodman is cited as one of the top bass fishing lakes in the United States.

The miscommunication between bass fisherman and environmentalists might be the crux of the issue, according to University of Florida historian Steven Noll, co-author of Ditch of Dreams, a natural and political history of the Rodman controversy.

Ecologists and those in favor of restoration, Carr explains, want anglers to realize that the banks will not disappear with the destruction of the dam. She believes that many fishermen have been given misinformation on what fishing conditions would be like without the dam.

“Both sides are using the same justification — they want to save the environment,” Carr says. “We all want to help the planet, but have different ideas of how to do that.”

Just as there are self-described environmentalists on both sides, there are anglers on both sides, too.

Erika Ritter grew up on the river; the Ocklawaha was her yard. She has fished there since she was 3 years old.

She was a kid when the “Crusher Crawler,” a machine designed to flatten about an acre of forest an hour, started clearing trees. She stood in front of it in an act of protest.

Now, Ritter captains tours down the Ocklawaha for her pontoon boat business, “A Cruising Down the River.” She doesn’t sugarcoat it for her passengers. She tells them about the sea lettuce that clogs the waterways and the crushed plant matter that floats up and smells.

“The water is tanned and stained,” she tells them.

Whenever she sees officers from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) she holds up a sign reading, “Bring back Striped Bass!”

“We’re trying to get our fish back, get that dam out of the way!” she yells.

Ritter can only give these tours every few years, when the Rodman Reservoir is in a drawdown —a period of active maintenance when the water level is lowered from about 18 feet to 11 feet, releasing 65% of the reservoir’s water. The drawdown brings the anglers, too, although there aren’t enough bass for anyone to keep what they catch. It also exposes the springs, and the remains of the cypress and other tree stumps that once held up a forest.

Ritter and Carr both refer to these dilapidated stumps as tombstones — reminders of a project that was never completed.

“The fact that [the dam] is an ecological destructive force for something that is completely useless is even more ironically sad,” Noll says.

But the fishermen wanting to keep the reservoir are Floridians, too. To them, home is the sound of water flowing through the dam and the feel of a bump on the fishing rod.

Richard Jones, a Putnam County resident, has been fishing at the Rodman Reservoir for 25 years. Rodman was a babysitter for his kids, a good way to pass the time and relax. He does not want to see the dam torn down.

“This is an opportunity for families to come picnic and teach their kids to fish,” he says.

Carr doesn’t believe recreation and conservation need to be mutually exclusive.

“Conservation needs to be made a priority,” she says in her opinion piece. “The recreation part will fall into place, a.k.a. ecotourism.”

While dams can benefit society, they also can cause considerable harm to rivers, according to American Rivers, which has tracked removal of 1,722 dams nationwide since 1912. Increasing numbers of dams have been removed from U.S. rivers over the century, including 90 dams in 2019.

Carr and others fighting for a more free-flowing Ocklawaha are pushing for a partial restoration plan. The Florida Legislature crafted a plan in 1993 to remove as few facilities as possible to restore the river to near pre-construction conditions, but 27 years later, that plan still lacks funding and permits.

Opposition for the plan led to a study in 2016 by the St. Johns River Water Management District to assess the possible effects that restoring the Ocklawaha would have on the St. Johns River in terms of nutrient deposits and destructive algal blooms.

“Monitoring data indicate that the availability of nitrogen alone (i.e., without the addition of phosphorus) does not encourage algal bloom growth in the freshwater reach of the lower St. Johns River and therefore does not constitute an adverse environmental impact from restoration,” the study found.

With these results, Carr states that the only thing stopping the restoration plan is political support and funding.

In order to get the necessary funding and political support to carry out the plan, Carr and her team encourage Putnam county residents to attend county commission meetings. The FDE has also made several trips to Tallahassee to present the pros of the plan.

Carr hopes that Gov. DeSantis will make the state’s environmental issues a priority.

The drawdown ended on March 1, and according to Carr, any new plants that sprouted will soon drown as water rises.