Watch above: Elizabeth Case shares her experience as a parent frustrated with how the school bus driver shortage in Alachua County has affected her family. (Gabriela Rodriguez/WUFT News)

Santa Fe High School ninth grader Cason Frey trudged one recent foggy morning with his military green backpack to his bus stop along State Road 121 in Gainesville.

For 30 minutes, Cason scrolled there through the Instagram app on his iPhone and/or watched the busy rush hour traffic speed by. Uncertain if his school bus would come, the 15 year old hurried back to his house, where it was safer to call his grandfather to ask for a ride to school.

Luckily, his grandfather could do so, but the boy arrived late to his first period class.

His mother Elizabeth Case, a dental hygienist, said she doesn’t have the type of job that allows her to leave work to take him to school whenever the bus doesn’t come. They must rely on relatives or friends to get him there, she said.

“It’s just put a really big burden on our family,” Case, 44, said.

School districts across north central Florida – and across the nation – are dealing with an urgent lack of bus drivers, which means each morning many students are left alone or in groups hoping their bus comes. Often, they are stranded at busy traffic intersections, and too often, their parents say, families must scramble to get them to their schools.

The problem exists in the afternoon as well.

Jacques Daniels, 17, a 12th grader at Santa Fe High, said when his bus doesn’t show up after school, he and other students are combined with those on another route.

“It’s too crowded to the point where some kids have to sit in the aisle,” Jacques said.

Alachua County Public Schools officials say they’re doing everything possible to have enough bus drivers to transport over 9,000 students across a total of 10,000 miles per day. As of this week, the district had a total of 116 bus drivers, down from 129 in 2019-20, officials said.

Drivers are quitting or staying away from routes because of, among other reasons, concerns stemming from the pandemic and an unwillingness to deal with students prone to cause trouble while on their busses. They’re also retiring because of advancing age, officials said.

The shortage is causing burnout among existing drivers – at least 36 have resigned in the past year – and forcing all district transportation department employees with a required license to get behind a school bus steering wheel is not sustainable, officials said.

They fear students will opt to not use the buses, which could lead to increased truancy; lost instructional time; equity concerns; loss of school funding – all of which lessen public confidence in the district overall.

“This is certainly a nationwide issue, and it is certainly the case here in Alachua County,” said Jackie Johnson, the district’s communications director.

Students and parents say it’s frustrating not knowing whether the bus will come.

Like most students each morning, Isabella Camacho, 15, a 10th grader at Santa Fe High, uses her cellphone to check the district’s website for notifications about late buses.

“If it’s 90 minutes or longer, it doesn’t come,” Isabella said. “It’s just another way of saying it’s not gonna come.”

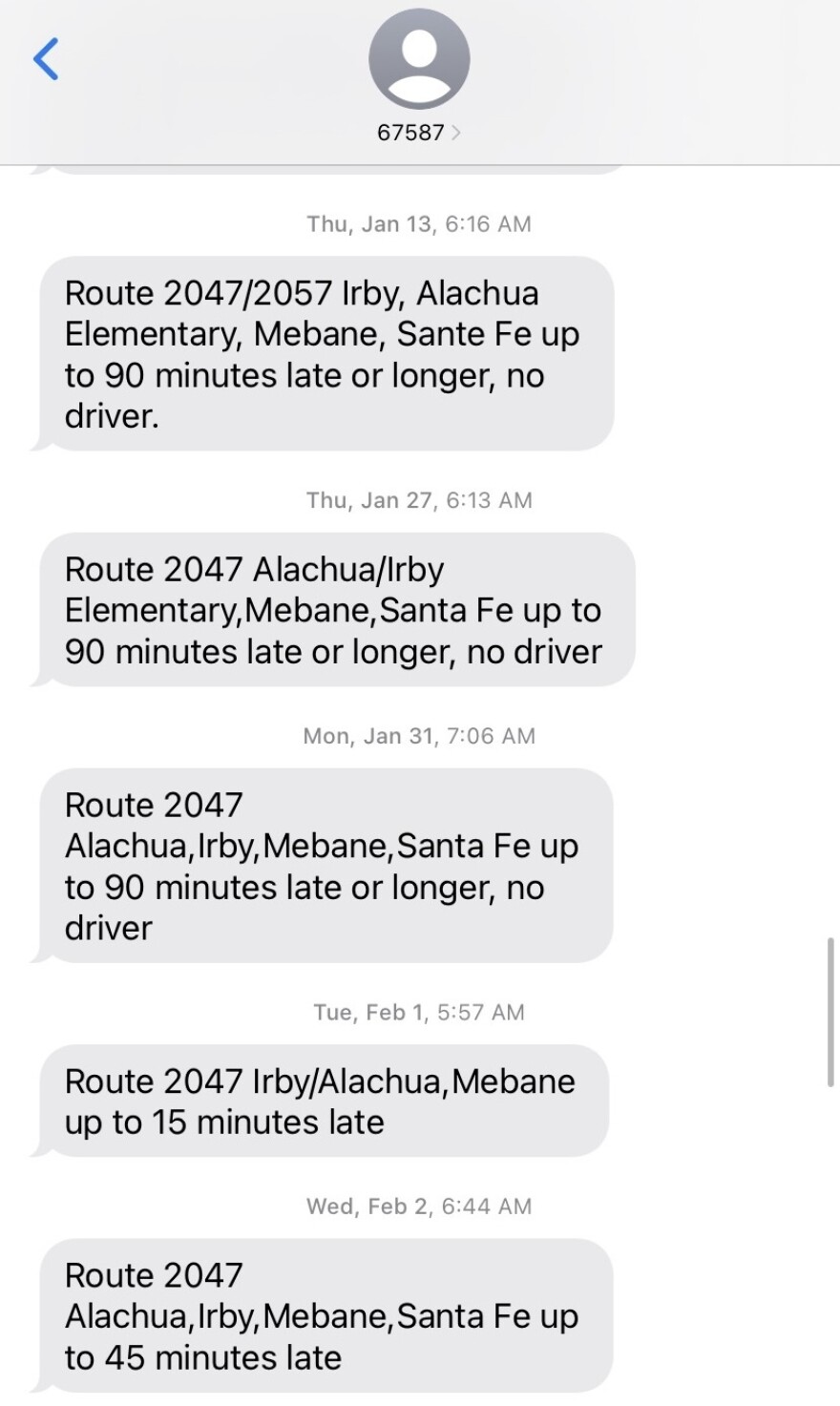

Parents can also register for Skylerts, which sends alerts when their child’s bus will be at least 15 minutes late. However, some parents said the alerts are unreliable.

Jennifer Cross, 48, a single mom of a Santa Fe High ninth grader, said after her son waited two hours for the bus too many mornings, it was easier to take him to school herself.

Cross said she can’t leave her job as a commercial printer to pick him up in the afternoon. She’s had to ask the transportation department to ensure he gets home. When the bus does come, Cross said he doesn’t get home until 6 p.m. – after getting out of school at 3:15. She said the bus ride is so long because his driver is doing different routes.

“My son is a high-functioning autistic child,” she said. “It’s ridiculous that we have to go through this.”

Michelle Vickers, 40, of Alachua, said she’s had to leave her job five times in the last two months to get her daughter, a sixth grader, from Mebane Middle School. A construction company marketing coordinator, Vickers said the situation is troubling.

“My daughter doesn’t even like to ride the bus in the morning anymore because, I feel like, it gives her anxiety,” she said. “She doesn’t know whether they’re going be there.”

Tiffany Castle, 52, a mother of a fourth grader at Newberry Elementary School and a sixth grader at Oak View Middle School, said when the bus is running late in the morning, she makes sure to get her daughters to school on time, leaving her late for work.

“I’m very inconvenienced, and I literally lose time at work, which is income,” said Castle, who declined to state her occupation.

Castle also said she’s quite concerned about the safety implications.

“It just is beyond frustrating to think of how many kids are sitting in places,” she said.

Alachua County school board member Mildred Russell said the driver shortage is “one of our most serious problems right now.” The district is advertising to fill positions on its website, and she’s personally reached out to people in hopes they would apply, Russell said.

“I’m hoping that we will be able to attract some new bus drivers, and then be able to, of course, get all of our students to school on time and to home again on time,” she said.

In December, the district and Alachua County Education Association, the union representing the drivers, agreed to increase starting hourly pay from $13.95 to $15.84, officials said. Still, said Crystal Tessmann, the union’s service unit director of the Alachua County Education Association, drivers are picking up more routes all year as well as more stress.

“If you don’t have enough bus drivers to start with, then you definitely can’t accommodate absences or time off,” Tessmann said. “And that’s definitely something that they have a right to have.”

Bus drivers who worked during the first semester of the school year also received a $1,250 bonus in their March 15 check, Johnson said. She also said drivers who go through an online security training and youth mental health training will receive an additional $1,000 bonus.

And, when necessary, transportation office employees will pick up routes if they are licensed to drive a school bus, and the district is also working on a plan to train employees at schools to work as bus drivers if they are available, Johnson said.

While parents say the transportation department isn’t helpful when they call its office, Johnson said it’s “working hard on that issue,” and that, “Part of the problem is, if you have office staff who are having to take on routes, that means fewer people answering the phones.”

Other school districts are also trying their best to respond to bus driver shortages.

“Typically, we need in the ballpark of 20-25 additional bus drivers on any given day,” said Kevin Christian, director of public relations for Marion County Public Schools.

Saying “the pandemic only compounded everything,” Christian said the school district recently hosted two “Bus Blitz” events to recruit drivers for open positions. Nineteen of the 119 people hired at a career fair on April 9 were bus drivers and five were bus aides, he said.

“We’re trying,” Christian said. “We invite those people who are complaining to become part of the solution and become a bus driver if possible. We are always looking for bus drivers. We are always hiring bus drivers. We always need bus drivers.”

Hernando County Public Schools is missing 30 bus operators out of its regular complement of 130, said Ralph Leath, the district’s transportation director. While facing the same challenges stemming from the pandemic and otherwise, Leath also cited student behavior as why some of trainees will realize the job isn’t for them.

“It’s a different generation, and that isn’t the whole reason, but that plays a part in it,” he said.

Union County Public Schools currently has enough bus drivers, though last year was difficult, said Tony Raish, the district’s transportation director. He said it wasn’t uncommon then to have drivers cover more routes, and for students to get home two to three hours late.

“The biggest thing that helped us out is our teachers are driving,” Raish said. “We have full-time teachers that are also full-time bus drivers.”

Raish also said being a smaller district helps. It needs just 20 full-time drivers to transport 1,500 students each day. Still, he said, there’s not a lot of leeway if someone calls out. When that happens, the district’s mechanics who are certified to drive school buses will cover routes.

Columbia County Public Schools will also have mechanics or substitute drivers fill in when needed. Daniel Taylor, the district’s transportation director, said with 56 drivers working, only two more drivers are needed to transport the 4,300 students who rely on its school buses.

“If it’s very bad or we’re desperate, then sometimes we split the routes up, but that has only happened twice this school year,” Daniel said. “I’m very fortunate.”

Levy County Public Schools has all of its bus driver positions filled, said Gary Masters, the district’s transportation director. He credits efficient hiring and training, and advertising on the district’s website and placing signs in public view across the county.

“We’ve been blessed to have enough drivers for every route and every trip,” Masters said.

The same is true for Clay County Public Schools.

“While we are still working to recruit and onboard additional school bus drivers, the district has implemented recruitment strategies on various platforms – both in-person and online – to fill the staffing needs experienced across the state and country,” Laura Christmas, the district’s communications and media coordinator, said in an email.

Back in Alachua County, the many parents left scrambling to find alternative ways to get their children to and from school are hoping for more solutions soon.

“I know that they’re shorthanded, and it’s not a good situation,” Castle said. “However, something has to be done.”