Their shoes slipping through yellow sand, Nancy Bissett and Steve Riefler followed an unpublished graduate thesis like a treasure map.

They snuck through a jumble of scrub oaks and evergreen shrubs. Emerging in a clearing on a bright March morning in the 1990s, they immediately knew they’d found it.

What the thesis had noted as a strange azalea was something altogether different: a sprawling, bushy plant that smelled unmistakably of toothpaste.

The pair had discovered what would later be identified as a new species in the mint family, Dicerandra modesta: blushing scrub balm.

Today, its last remaining wild population exists only where Bissett and Riefler found it: on a sandy slope at the edge of the Lake Marion Creek Wildlife Management Area in Polk County.

Soon, it might not exist at all.

Draft routes for a toll road connection to Interstate 4 cut straight through the plant’s habitat or close enough to interfere with its management. They make a beeline for Bissett’s 10-acre wholesale plant nursery, too, splitting the 43-year enterprise in two and eliminating nearly half its growing area.

The routes are preliminary. Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise has yet to decide which is best or if it’ll even pursue the project. But with Polk County leading the state in population growth, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to avoid pink blooms and verdant stems.

It’s Florida Department of Transportation policy to avoid, minimize and as a last resort, offset environmental impacts, but plants don’t get the same habitat safeguards that animals do. The agency’s internal guidance states it’s “often not obligated to protect,” threatened and endangered plants.

The lack of standardized protections leaves rapidly developing regions across the state to grapple with a thorny issue: how to keep native plants growing when the population is, too.

Growth in the Heartland

If central Florida is the state’s heartland, Polk County is its pacemaker.

It's the fastest-growing county in the state, bridging Tampa and Orlando with an ever-increasing array of houses and shops amid scrub land and ranches.

Polk County’s population — estimated last year around 850,000 — is expected to top 900,000 in the next five years and one million in the next 15, according to medium-growth modeling by the University of Florida’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research.

Increasingly, new arrivals are forgoing the historic hotspots of Lakeland and Winter Haven in favor of towns nestled in the northeast third of the county: a morning’s commute from Disney World.

The roads aren’t ready.

“We’re seeing a real rush and need,” said Ryan Kordek, Executive Director of the Polk Transportation Planning Organization.

U.S. Route 27, the region’s main north-south thoroughfare, averages 75,000 cars daily in both directions. It’s one of the top roads in the county for traffic injuries and fatalities. U.S. Route 17, I-4 and two-lane country roads accommodate the rest of the travelers but with frequent congestion.

If there's one area in the county that needs more roads, Kordek said, it’s the northeast.

The Florida Department of Transportation agreed.

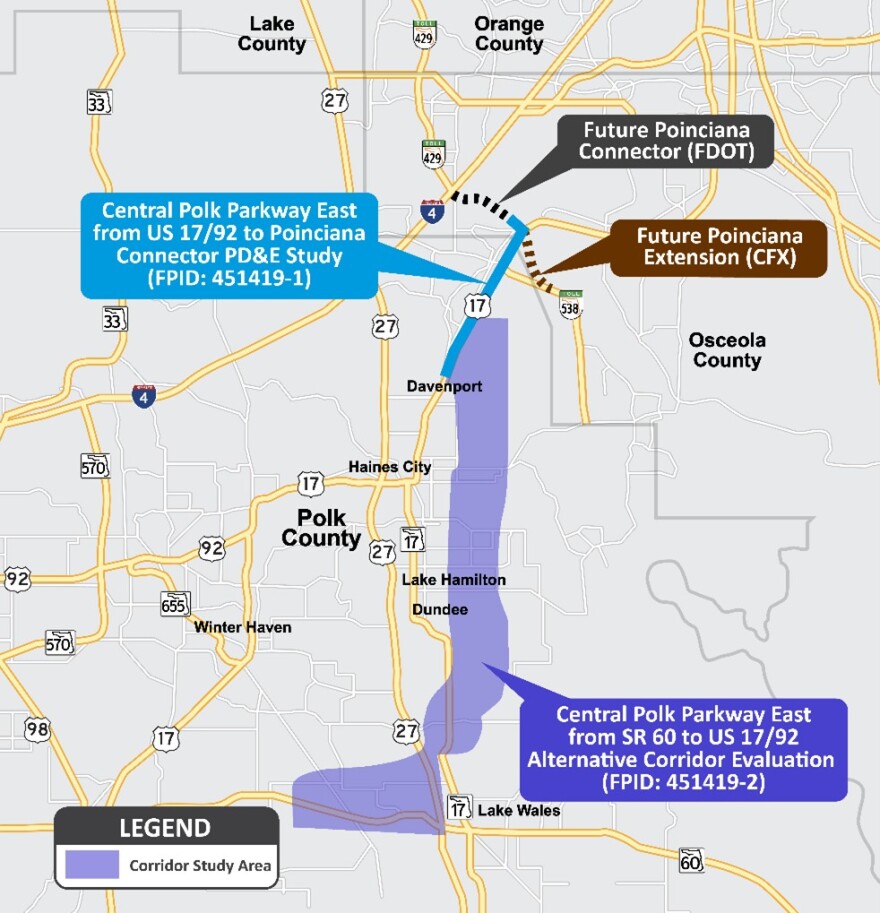

It approved a path for a J-shaped tollway in 2011, connecting state Road 60 to state Road 570 to the west and U.S. Route 17/92 to the north. Construction on the western portion is underway, but “substantial development along the approved alignment” pumped the brakes on the eastern leg.

Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise, a unit of FDOT, resumed the project last May, launching an alternative corridor study for the 28-mile eastern segment known as Central Polk Parkway East.

So far, its proposals have been met with sharp environmental criticism. But Kordek, whose team sees a flurry of comments about relieving congestion on U.S. 27 each time it solicits public comment, is hopeful FDOT will find “a solution to everyone’s benefit.”

The plant in a parkway’s path

Even among endangered plants, the blushing scrub balm is exceedingly rare.

Conservationists keep the plant’s exact location within the Lake Marion Creek Wildlife Management Area quiet for fear that public visits — however well-intentioned — could destroy it.

Their caution hasn’t saved the species from disturbance.

A power line carved through the plant’s habitat in the 1970s.

A natural gas pipeline went in beneath it in 2016.

Crews now routinely mow and spray herbicide along the pipeline’s path to make way for inspection and maintenance, destroying swaths of scrub balm in the process.

University of Florida Assistant Professor Raelene Crandall surveyed the area stem by stem in 2018, counting 2,200 blushing scrub balm plants.

When research contributor Todd Angel went to the site to monitor the plant’s population in 2022, he found their flags destroyed and “thrown a distance from their plants,” victims of a mower’s blade.

“Population size has been declining each year for at least five years, especially where mechanical treatment and fire are absent,” wrote Crandall in her 2024 progress report on the species. “If this pattern persists, D. modesta is likely to become locally extinct.”

The pipeline and powerline make it difficult to do prescribed burns: a necessary “reset” to keep native plants healthy and invasive ones out. The tollway, which, in the two current proposals, would come within 500 to 1,500 feet of the blushing scrub balm, would make it nearly impossible.

Though too close for comfort, the remaining proposals are better for the scrub balm than most previous ones, which would’ve paved right through the population’s center. Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise discarded those options to accommodate recently approved developments and concerns over impacts to wildlife and views in Bok Tower Gardens.

FDOT policy doesn’t require the agency to avoid native plants or their associated habitats during the planning, design or construction processes.

Though federally-listed plants including the blushing scrub balm are protected by the Endangered Species Act, “destruction, damage or relocation of protected plants is not prohibited unless these activities take place on federal lands,” according to the agency’s project development and environmental manual.

“These listed species generally are not afforded the type of protection that listed wildlife are,” reads additional internal agency guidance, “so FDOT is often not obligated to protect these species when they occur within transportation right of way.”

Reflecting on a task force for a different proposed toll road project in 2019, Florida Native Plant Society President Eugene Kelly wrote, “while harboring no hostility whatsoever towards the Florida Panther, Sand Skink, Manatee, or any of the other listed animal species being given proper consideration, I was squirming in my seat and fighting the urge to say aloud ‘what about the plants!’”

The agency’s rules reflect a larger pattern in endangered species conservation. More than half of the species listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act are plants, yet they only receive 6.6% of funding from government agencies and nonprofit organizations.

Researchers dub it the “beauty bias.”

Flashy, familiar species earn public support and research dollars while the creepy, crawly and faceless go underprotected. In one survey, participants were more willing to protect plants when they appeared with pollinators, leading researchers to conclude that picturing flora with butterflies and birds could be a legitimate conservation strategy.

A spokesperson for FDOT declined WUFT’s request for an interview and wrote in an email, “further surveys and coordination with rare plant experts and local ecologists will continue through the Design and throughout future phases of the project to avoid and mitigate impacts on sensitive species.”

Valerie Anderson, communications director for the Florida Native Plant Society, said the organization received no response to a letter it sent to FDOT in May.

The two groups have previously partnered in so-called “plant rescues” to relocate species in development’s way. Such rescues target individual plants, not whole ecosystems.

“You’re not making a new island with a whole intact population,” Anderson said. “You're destroying habitat and then moving that plant to a different location in isolation. It’s doable, but certainly an action of last resort.”

The species has one more backup. About 5,000 of its seeds wait in long-term storage at Bok Tower Gardens, 25 miles away. They were secured there in 2023 as part of a statewide effort to safeguard rare plants from extinction.

But if land managers have to tap into this precious reserve to keep the species alive, “where are you going to put it?” asked Anderson. “How is that going to be protected any more than this area is protected?”

When “perpetuity” has an end date

While the most recently proposed corridors for Central Polk Parkway East dodge the scrub balm’s habitat, they cut straight through Nancy Bissett’s nursery.

It’s a difficult topic for her to discuss, one she said has caused “many sleepless nights.”

Bissett and her husband, Bill, have run the Natives Nursery for 43 years. They grow native wildflowers, grasses and shrubs for restoration and wholesale projects. The pair has aided in mitigation efforts for wetlands across the state, but never imagined their property would be the one in development’s path.

The couple hosted the tollway’s coordinator, Jazlyn Heywood, who told them she’d received many comments in support of the nursery but the project was “tending to proceed anyhow,” Bissett said.

“They’re saying it’s their option,” she said of the route cutting through her nursery, “I do not believe it’s the only option.”

The Bissetts thought their land was protected. They sold the property’s development rights decades ago, securing it under three conservation easements.

Though marketed as permanent, conservation easements can be undone. The Central Florida Expressway Authority bought land protected under an easement from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Osceola County for a toll road project last May.

It offered 1,500 acres of conservation land in exchange for 60 acres through Split Oak Forest, a deal some environmentalists say wasn’t as attractive as it seemed because of impacts to gopher tortoise habitat.

“We just weren't aware that could happen,” said Kristen Nowak, President of the Board of Directors of Green Horizon Land Trust, which owns one of the Bissetts’ easements. “Conservation easements are a big deal, so we thought that would be an automatic ‘avoid.’”

Henry Pinzon, an environmental management engineer with Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise, assured listeners in a May 5 information session the designs “identified and minimized” impacts to conservation easements, though Florida statute allows for their release when “unavoidable”. If a landowner doesn’t agree to sell, the agency can invoke a legal process known as “eminent domain” to claim the land for public use and pay the owner fair market value.

In hearing from other land trusts confronted with development pressures, Nowak said the outlook is bleak. “Eminent domain is pretty strong for transportation,” she said.

As for Bissett’s easements, rare plants and business, “they just say it's taken into consideration,” she said.

Is it frustrating?

“You have no idea,” Bissett said.

A better way to build

While some environmentalists hope for a “no-build” alternative, others say smart planning could overcome environmental tensions.

Paul Owens is president of 1000 Friends of Florida: a Tallahassee-based nonprofit advocating for environmentally and fiscally responsible growth management statewide.

The group was involved in planning discussions and later opposed the M-CORES project: a series of three toll highways mandated by Florida law in 2019 and repealed in 2021.

What M-CORES got wrong, Owens said, was cutting corners on safeguards to protect natural resources and “to prevent uncontrolled development that could otherwise be spawned by the new highways.”

Wekiva Parkway, on the other hand, got those elements right.

“From the get go, they put a priority on protecting the environment,” Owens said. FDOT and the Central Florida Expressway Authority opened the final segment of the $1.6 billion project last year.

Before the project broke ground, the agencies secured 3,400 acres of conservation land in the parkway’s path to prevent roadside development. They elevated segments of the road to allow wildlife to cross safely beneath, limited interchanges in natural areas and designed bridges to limit runoff into the Wekiva River.

While widely heralded as model practices, those measures are expensive.

Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise considered building an elevated roadway on U.S. Route 27 for the Polk County project in 2018, but concluded it wouldn’t be cost feasible.

If Central Polk Parkway East moves forward, project managers will consider other environmental safeguards later in the planning process.

The only task they face now is deciding on a corridor.

Advocates hope it will be one that allows both Bissett and the scrub balm to stay rooted in their Polk County homes.